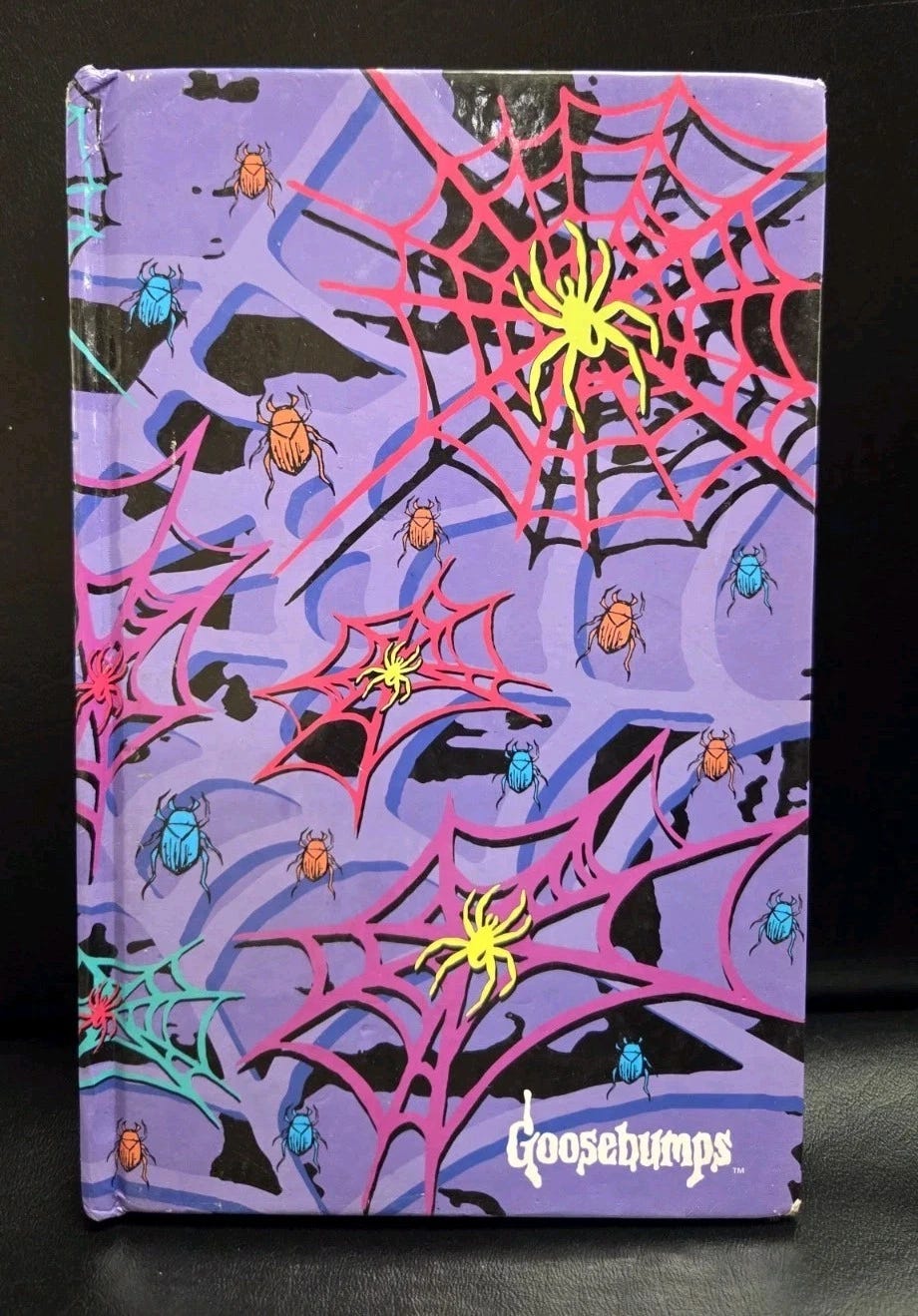

The sound of tape stretching across corrugated cardboard reverberated through the almost empty room. I sealed the box I’d just packed and pushed it against the wall when I heard my mom giggling in the closet. She was pulling notebooks and photo albums off the shelf and she’d uncovered an old journal from when I was in middle school. It was one of those little 5.5” x 8.5” printed label journals, with a little silver latch, lock and key attached by a clear, thin plastic tie. These little journals were a dime a dozen at your local big box store and came in a variety of themes—the Powerpuff Girls, Batman, Looney Tunes, you name it. Mine was purple and red, wrapped in a repeating pattern of spiderwebs with a Goosebumps logo anchored in the corner.

In this small journal was one entry:

“Dear God,

I wish I was Goku so I could fly.”

My mom had only a vague notion of who Goku was, the leading character in the popular anime series that I loved, but the entry tickled her, and she’s teased me about it for years.

It surprised me at the time that I wasn’t embarrassed. I was completely comfortable writing my innermost thoughts on paper even if that meant someone could read them. What I didn’t realize then, was that writing was therapeutic for me. It was the outlet I needed to expel all the words in my head that I would never say out loud.

I’ve always felt a little split—divorced from my authentic self in a way. By that I mean, I present as outgoing, but I live so much of my life internally. I’m one way in a crowd and another alone. I don’t doubt this is true of everyone, but when I was younger that realization made me feel alienated. Thinking that everyone else was their true selves all the time, and that I was living some kind of lie really bothered me. I was blessed to be surrounded by what I determined to be very genuine people, and here I was, masking my thoughts, not saying what I meant in the way that I meant it. I had the vocabulary, but I didn’t have the confidence.

Journaling was the only outlet for the real me, for all the things I had to say but couldn’t say or wouldn’t say. I would spend hours writing. I’d take my journal everywhere. Whether I was sitting at a bar, on break at work, walking to the store, my journal was with me. I’d have a thought mid-motion and stop to write it down. When I couldn’t process an experience in my mind, I’d write my way through it. I became adept at memorizing whole exchanges between friends or random people I’d met on the street. I’d write about what they were wearing, or the way they moved their hands while speaking. If their eyes fluttered or darted from one person to the next, I’d write it down. The more I wrote, the more my attentiveness to others inadvertently increased. My ability to dissect and describe situations developed and became more complex. I would extrapolate outward to try to anticipate what the other person was thinking and feeling.

Despite the post-present nature of writing, namely that I had to reflect on an experience to process it, write about it, give words to it—journaling made me more present. Where I couldn’t connect before, writing now anchored me to reality. It imbued every interaction with new purpose and the excitement of discovery through recall had poetic meaning for me. By the time I hit thirty and I was staring down a box filled with journals that captured the last decade of my life, I realized that journaling wasn’t just a private act anymore, it was my reality. It was how I learned to let go. Every time I wrote, it felt like I was pulling heavy emotions out of my body and leaving them on the page and that weight lifted me, made me feel clearer and lighter, and gave me the space to move through the world without being so tangled up inside myself. Writing taught me how to put shape to the thoughts in my head and how to speak more openly and honestly with others. What began as an unconscious way for me to process what I couldn’t say out loud slowly turned into a set of tools I could use to communicate in real time.

The irony is that the more I leaned on journaling, the less I actually needed it. Writing so much no doubt made me a better writer, but it also made me better at living. It trained me to express myself without always reaching for a notebook, to trust that I could handle conversations as they happened. That old Goosebumps journal only held one short seemingly meaningless entry, but I think that first act of committing thought to paper planted a seed in me. My desire to fly wasn’t about wanting to escape, but a desire to see the world fully, to observe more clearly.