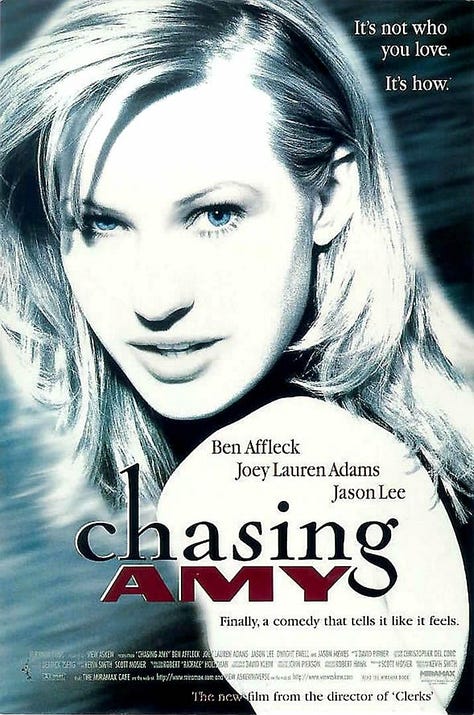

Smith’s Chasing Amy Has Nothing to Say, But Says It Loudly

The cult-classic romantic comedy is neither romantic nor comedic. It’s a cautionary tale of arrested development disguised as a story of sexual awakening.

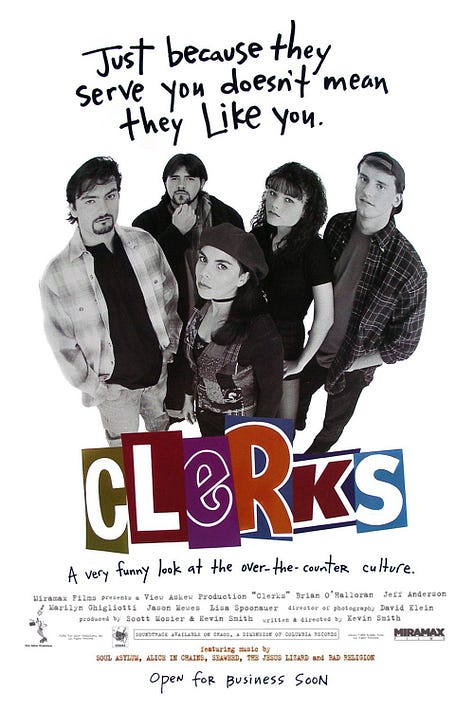

Kevin Smith is a capable director. His writing can be smart, even quite witty, and Clerks, his breakout feature, does feel inventive even if not wholly lovable. But Chasing Amy, the film often heralded as his emotional turning point,1 is something else entirely: a story so mean-spirited toward the queer community that it’s hard to believe it was ever intended to do anything positive.

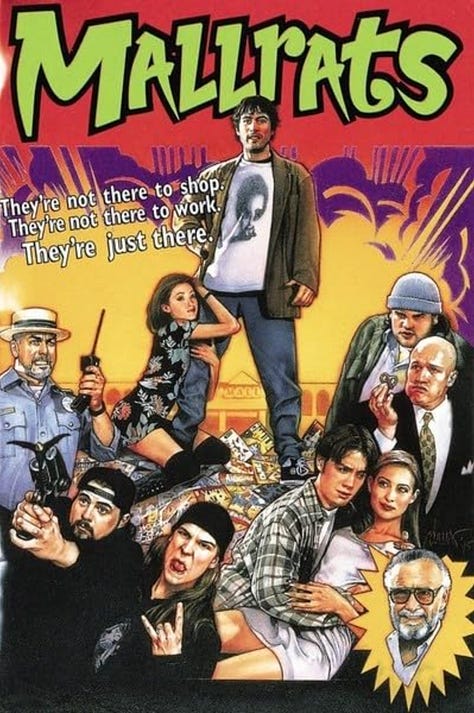

Released in 1997, Chasing Amy is the third installment in Kevin Smith’s View Askewniverse,2 following Clerks (1994) and Mallrats (1995). While it features returning fan-favorite characters like Jay and Silent Bob, the film marks a tonal departure from its more comedic predecessors. The story centers on Holden McNeil (Ben Affleck) and his best friend Banky Edwards (Jason Lee), two aspiring comic book creators trying to find their footing in adulthood. At a convention, they meet Alyssa Jones (Joey Lauren Adams), a fellow writer who identifies as a lesbian. Despite her sexual orientation, Holden becomes infatuated with her and pursues a deeper connection. To his surprise, Alyssa reciprocates his feelings, sparking a complicated romance that challenges them both. Banky, uncomfortable with their relationship and increasingly jealous of Holden’s shifting priorities, grows resentful. Convinced that Alyssa is threatening everything he and Holden have built together, Banky reveals a damaging secret that ultimately unravels the couple’s fragile bond.

In the larger context of Smith’s View Askewniverse, Chasing Amy feels like a misstep. While Clerks and Mallrats had their share of flaws, they offered sharper, more relatable insights into the absurdity of growing up anchored by humor, irreverence, and a kind of scrappy charm the audience could resonate with. Smith’s minimalist production design and dialogue-heavy style worked in those films because the conversations felt authentic, and the characters’ awkwardness was met with empathy and satire. But in Chasing Amy, those same techniques only serve to magnify the film’s shortcomings. The spare visual style—static shots, tight framing, unembellished sets—leaves the audience with nowhere to look but the script, which falters in its handling of identity, queerness, and intimacy. Instead of interrogating Holden’s fragile masculinity and homophobia, the film frames him as a tragic figure, a man-child undone by love. His self-pity and insecurity are treated as the central emotional arc, but his inability to accept Alyssa’s queerness reads less like character growth and more like unchecked entitlement.3 Without the humor or tonal self-awareness that softened the rough edges of Smith’s earlier work, Chasing Amy feels emotionally lopsided and culturally disconnected.

There’s a version of this story that could have worked. A straight man falls for a queer woman, is challenged by the limits of his perspective, and grows through the painful process of realizing that his love does not entitle him to reciprocity. But that is not the film Smith wrote. Instead, Chasing Amy offers up Holden as a kind of emotional bulldozer. He sees the world through the tiniest of pinholes, and when something lies outside that narrow view, he lashes out. His behavior is framed not as toxic, but tragic.

There’s no mistaking the allusion: Holden, like his namesake Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye, is self-righteous and painfully out of his depth. But where Salinger’s character is a portrait of adolescent disillusionment, Smith’s Holden is simply a grown man clinging to juvenile delusions about sex, love, and control. The difference is critical. The former is a study of grief and confusion while coming of age; the latter highlights the tantrums of a grown man when things don’t go his way.

What’s most frustrating is not that Holden is flawed, flaws make characters interesting, but that the film doesn’t hold him accountable, offering no redemption arc or real growth. In one of the film’s rare flashes of insight, Alyssa scolds him in the rain for acting unfairly by asserting his desires without regard for hers. “People change,” he exclaims, “there’s always a period of adjustment.” To which Alyssa retorts, “Period of adjustment? There’s no period of adjustment, Holden, I’m fucking gay!” It’s a brilliant confrontation, the kind of scene that feels too precise to be accidental. But instead of deepening the conflict or exposing the systems of entitlement Holden represents, the film backs away.

The fight in the parking lot after the hockey game, where Alyssa unleashes a visceral, full-bodied rage at Holden, feels like the emotional climax the film so desperately needs. Her fury, raw and unfiltered, seems to speak not only for herself but for every woman exhausted by the emotional labor of explaining their boundaries to fragile, entitled men. The blocking in this scene has Alyssa pacing, physically asserting space as Holden stumbles after her and it visually reinforces the power dynamic she’s rejecting. For once, the static framing and Smith’s minimalist style work in the film’s favor, allowing Alyssa’s body language to carry the weight of what the script itself can’t quite articulate. It’s the most honest moment in the film, and for a brief second, it seems Smith might finally be steering toward a real critique of toxic masculinity and the cultural delusion of “converting” a gay woman through straight male longing. But that promise evaporates quickly. Rather than serving as a turning point, the scene is undermined by a painfully misguided finale in which Alyssa inexplicably offers Holden closure, not from a place of agency, but from what feels like emotional exhaustion. She’s written into a corner, forced to extend grace to the very man who refused to meet her where she stood. The potential for pointed commentary dissolves into the soft haze of hetero reconciliation, dulling any edge the film had briefly sharpened.

Holden’s inability to handle Alyssa’s past, his knee-jerk reaction to her sexual history, his need to assert control, becomes a mirror for a much larger issue: the film’s fundamental misunderstanding of queerness. It’s not about preference, or fluidity, or connection. It’s about conquest. Alyssa isn’t treated as a full person, but as a prize to be won, one whose queerness exists only to be challenged, and ultimately, erased.

This would all be frustrating enough if it were unintentional. But Chasing Amy often feels like it knows exactly what it’s doing, and that’s what makes it worse. Its central conceit hinges on the dangerous, long-tired trope that a queer woman just hasn’t met the “right guy” yet. That all she needs is some “serious deep dicking”—a line so grotesque, so confidently delivered, it betrays the film’s full hand. These are not the words of a writer trying to dismantle stereotypes. These are the words of someone comfortable reinforcing them.

And while Chasing Amy may try to pass itself off as progressive for its time, it lands with the force of something far more regressive. There’s no lesson here, no consequences, just a series of increasingly painful choices that leave the viewer with little more than a lingering sense of discomfort.

What makes it all the more jarring is how tonally deaf the performances often are. There’s no charm, no chemistry, just shouting matches and one-dimensional brooding. Adams tries her best, imbuing Alyssa with flashes of depth, but she’s given so little room to breathe that her arc feels preordained. Affleck, meanwhile, performs Holden with the kind of earnestness that only amplifies the character’s worst qualities: the self-importance, the pouty insecurity, the simmering entitlement. It’s not a romantic comedy. It’s a psychological case study in male fragility.

Rarely does a film elicit such vehement dislike, but watching this unfold, waiting for a turn that never comes, feels like watching a door close that was never really open in the first place. It’s hard to imagine a world in which a character like Holden is considered charming, desirable, or even tolerable. His failings are never explored, only indulged.

Smith’s universe of characters, which many hold dear, can sometimes feel like a boys’ club afraid of its own limitations. And Chasing Amy may be the most telling example of all: a film that believes it’s starting a conversation, when in fact it’s talking over the very people it claims to represent.

There’s anger in this viewing experience,4 yes, but not the kind the film hopes to provoke. It’s the anger of recognition, of hearing something deeply familiar and equally exhausting. The notion that queerness is up for negotiation, that it’s a phase, that love, when it comes from a man, must always win.

Chasing Amy is not just a product of its time. It’s a product of its creator’s blind spots.5 And for all its smart dialogue and self-aware posturing, it ultimately says very little about love, identity, or growth.

It only knows how to shout.

Notes

In Rolling Stone, Peter Travers called it “very good indeed.” Empire gave it a 4 out of 5 stars. Roger Ebert called it, “a big step ahead [for Smith] into the ranks of today’s most interesting new directors.” And it currently sits at 87% on Rotten Tomatoes.

The View Askewniverse is Kevin Smith’s shared cinematic universe, encompassing interconnected films like Clerks, Mallrats, Chasing Amy, and Dogma. Centered in New Jersey, it features recurring characters, especially Jay and Silent Bob, and explores themes of friendship, pop culture, and working-class life with a blend of crude humor and emotional depth. The universe includes meta-commentary on film, comic book culture, and spirituality, often through slacker antiheroes. It’s cult following and indie spirit has evolved over decades, culminating in self-referential sequels like Jay and Silent Bob Reboot and Clerks III.

Cammila Collar offers a strong, balanced analysis of male privilege in her piece on Medium, though her subtitle, “How Kevin Smith’s 1997 comedy was way ahead of its time,” and overall thesis still give Smith more credit than I believe he deserves.

Bi-fem writer, Shana, gives us a visceral perspective of her viewing experience in 2022 for Autostraddle.

Director Sav Rodgers, whose TedTalk inspired the feature-length documentary, Chasing Chasing Amy, interviews actress Joey Lauren Adams for the film. In a candid moment, Adams reveals that Chasing Amy serves as a window into the insecurities Kevin Smith projected during their real-life relationship. She reflects, “He made me feel bad for living the life I had lived and being who I had been because he was insecure.” Her interview not only reframes the film’s narrative but also sheds light on the emotional cost behind its creation.