As someone who works in publishing, I’ve seen firsthand how stories shape public understanding. The narratives we elevate influence how people think, vote, and respond to critical issues especially when it comes to complex policy decisions like environmental regulation. That’s why I’m writing to fellow editors, journalists, and media professionals because we have a responsibility to tell the full story behind President Trump’s March 2025 executive order to “Immediately Expand American Timber Production.”1

At first glance, the order appears to promise a practical economic boost by cutting the red tape, unleashing U.S. industry, and creating jobs.2 But beneath that surface lies a sweeping erosion of environmental protections. The directive instructs agencies to “eliminate . . . all undue delays” and “suspend, revise, or rescind” any regulation seen as burdensome to timber production. In plain terms: it invites industry to bypass decades of legal safeguards that protect our national forests’ health, accessibility, and resilience.

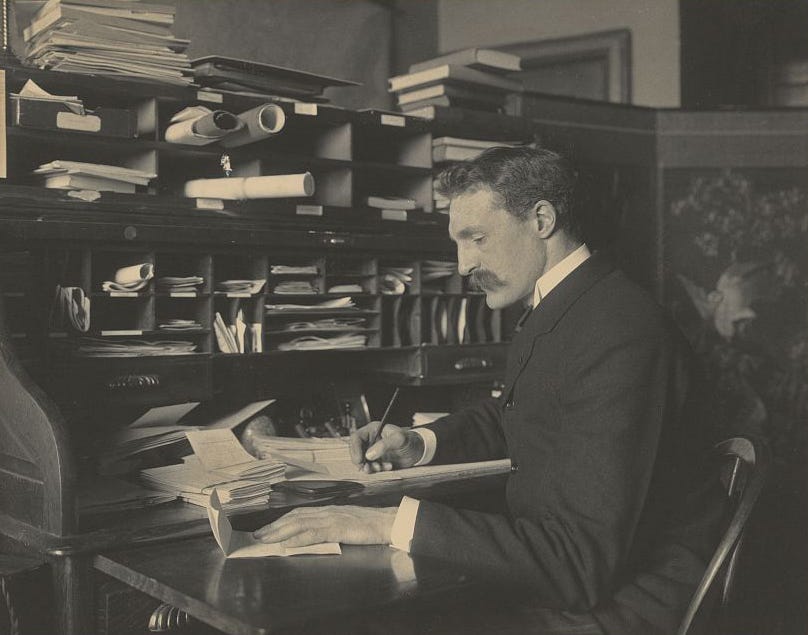

This isn’t just a policy shift—it’s a rupture in over a century of conservation ethics rooted in leaders like Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of the U.S. Forest Service. Pinchot believed public lands should serve “the greatest good for the greatest number in the long run.” Our forests are far more than lumber stockpiles; they are ecosystems, carbon sinks, water sources, and economic lifelines for rural communities. They are part of our national story.

The damage this order threatens goes beyond deforestation. It undermines foundational laws like the National Environmental Policy Act3 and the National Forest Management Act,4 which were designed to ensure transparency, public input, and long-term planning of how U.S. public lands should be managed under a multiple-use mandate.5 The idea that our forests should be managed wisely, not plundered for short-term profit, is a principle that has guided bipartisan stewardship for generations. Abandoning it now would be not only reckless, but irreversible.

I think the numbers tell a sobering story. In 2015, National Forests supported 2.4 million livestock animals, while tourism and recreation generated billions annually for rural economies. Logging without adequate oversight jeopardizes these revenues by degrading soil, reducing water quality, destroying habitats, and increasing wildfire risk.And the promise of economic relief? It’s often hollow. Timber jobs tend to be temporary and subject to automation and outsourcing. Forests, once stripped, don’t bounce back on demand.

The administration frames this order as an economic solution, when it's really a distraction from deeper problems. Rather than addressing the flawed trade policies that sparked tariffs on U.S. timber and paper—while conspicuously exempting books to avoid a slew of lawsuits from the Big Five publishers—the order sacrifices public land in a misdirected bid for recovery. As the American Booksellers Association pointed out in April, this strategy does nothing to address root economic failures. Instead, it doubles down on them.

Legal challenges are already underway. The Center for Biological Diversity and other environmental groups have cited violations of federal law and lack of public input.6 But while the courts sort through the legal complexities, the media has a more immediate task: helping the public connect the dots. This is not just about trees. It’s about whether we manage public resources with integrity or treat them as political collateral.

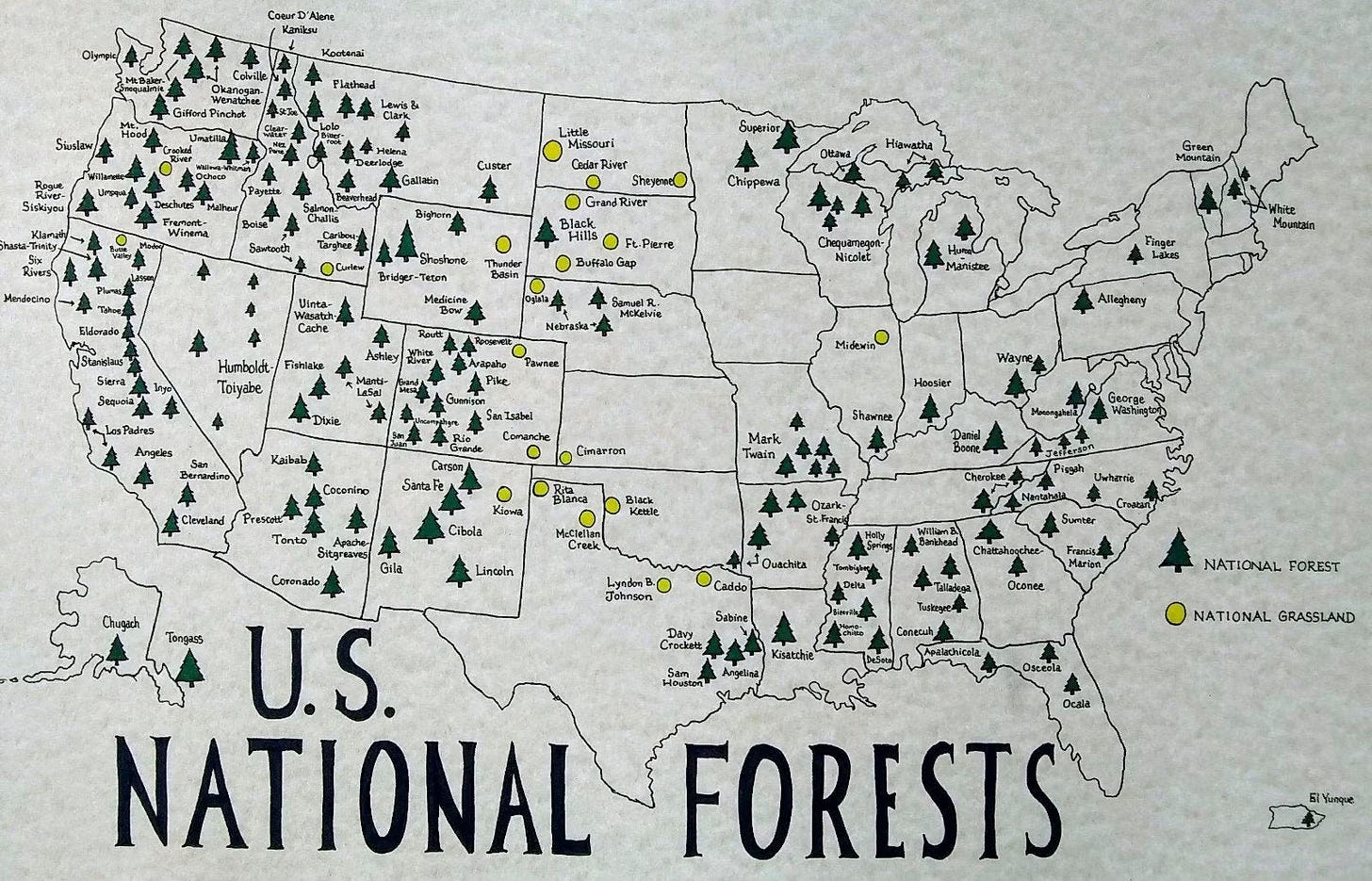

To be sure, some argue that deregulation is necessary to stimulate growth in struggling rural areas. They point to global market pressures, high unemployment, and bloated federal processes. These concerns deserve acknowledgment, but they don’t justify dismantling the very framework that keeps our forests sustainable. We can, and must, invest in rural communities without gutting environmental oversight. The Forest Service’s long-standing model of multiple-use management allows for logging, yes, but also for grazing, recreation, and conservation. That’s the kind of balanced planning that sustains both jobs and landscapes for generations.

This is a call to my colleagues in media and publishing to tell these stories with clarity and courage. We must hold policymakers accountable when they use crisis as cover for exploitation. And we must remember that journalism is not just a profession, but a form of public service.

Reversing this executive order would serve the public in so many way, especially as a recommitment to stewardship, public trust, and the ethical imperative to see beyond short-term solutions. Let’s make sure that’s the story we’re telling.

References

American Booksellers Association. Economic Impacts of Trade Policies on Timber Markets. 8 Apr. 2025, https://www.bookweb.org/news/overview-2025-tariffs-1631822.

Center for Biological Diversity. Legal Challenge to Executive Order on Timber Deregulation. 2025, https://www.biologicaldiversity.org.

Fedkiw, John. The Evolving Use and Management of the Nation's Forests, Grasslands, Croplands, and Related Resources. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-GTR-175, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, 1989. https://www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs_series/rm/gtr/rm_gtr175.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture. National Forests and Rangelands: Economic Contributions to Agriculture. 2017, https://www.fs.usda.gov/emc/economics/documents/at-a-glance/benefits-to-people/nfs/BTP-NationalForestSystem.pdf.

USDA Forest Service. History of Forest Management and Conservation Principles. n.d., https://www.fs.usda.gov/learn/our-history.

The White House. Executive Order on the Immediate Expansion of American Timber Production. 2 Mar. 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/immediate-expansion-of-american-timber-production/.

Images

Figure 1. Johnston, Frances Benjamin. Gifford Pinchot. Between ca. 1890 and ca. 1910. Photographic print. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. https://lccn.loc.gov/200170409.

Figure 2. MediaevalMapmaker. U.S. National Forests Map. Etsy, https://www.etsy.com/shop/MediaevalMapmaker.

Notes

In March 2025, President Trump issued Executive Order 14225, directing federal agencies to rapidly expand timber production on public lands by streamlining environmental reviews, fast-tracking forest thinning, and setting aggressive annual harvest targets. The order cited wildfire prevention and economic growth, while invoking emergency powers to override Endangered Species Act protections in certain cases. Supporters, including logging industry groups, praised the move as a boost to rural jobs and domestic supply chains. Critics warned it threatened ecological stability, endangered species, and could increase wildfire risk. A related directive also launched a Commerce Department investigation into foreign timber imports, laying groundwork for possible tariffs.

According to the American Forest & Paper Association (AF&PA), the U.S. forest products industry employs more than 925,000 people, largely in rural America, and is among the top 10 manufacturing sector employers in 44 states. The industry accounts for approximately 4.7% of the total U.S. manufacturing GDP, manufacturing more than $435 billion in products annually.

Passed in 1969 and signed into law in 1970, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was the first major environmental law in the U.S. and is often called the "Magna Carta" of federal environmental policy. NEPA requires federal agencies to evaluate the environmental impacts of major projects—like building highways, pipelines, or dams—before making decisions. It aims to ensure that development happens in a way that balances environmental protection with economic and social needs. NEPA also helps keep the public informed and involved, and its framework has influenced environmental laws in many other countries.

Passed in 1976, the National Forest Management Act (NFMA) guides how national forests are managed, requiring the U.S. Forest Service to create long-term plans that balance logging, recreation, wildlife protection, and other uses. The law was a response to concerns about over-logging and clear-cutting, and it ensures that forests are managed sustainably to protect both natural resources and public interests.

The Evolving Use and Management of the Nation’s Forests, Grasslands, Croplands, and Related Resources (USDA Forest Service, 1989) offers a comprehensive overview of how U.S. public lands have historically been managed under a multiple-use mandate—balancing timber harvesting with conservation, recreation, and watershed protection. Referencing this report underscores how today’s deregulatory actions break with decades of policy grounded in ecological sustainability and long-term public benefit.

In May 2025, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a lawsuit using the Freedom of Information Act to demand records from several federal agencies—including Interior, Commerce, and the Forest Service. They argued that these agencies haven’t been transparent about how the executive order to increase logging and ease environmental rules is being carried out, which they say breaks the law and shuts out public input. Along with Earthjustice, they also claim the order’s fast-tracked logging plans ignore important protections under the Endangered Species Act and NEPA, go beyond the president’s authority, and put wildlife and ecosystems at risk.