Introduction

Crowd Control1 began as an open mic event at Mudsmith, a coffee shop on Lower Greenville in Dallas, Texas, before moving to the rooftop of Sundown at Granada. As a co-founder2 and participant, I viewed Crowd Control as an opportunity to cultivate a creative space that reflected what Senda-Cook describes as “the creation of rhetorical cartographies by those who live in, make use of, and aim to reimagine space/place, especially urban space/place.” This analysis explores how we reimagined urban space as a site for artistic expression and community-building, creating an environment where diverse voices could be amplified. Through a cultural rhetorics lens, I examine how Crowd Control resisted hegemonic structures related to gender, class, and race by fostering a participatory culture that challenged the limitations imposed on Dallas’s arts scene between 2016 and 2019. Drawing on rhetorical cartographies, discourse community frameworks, and participant reflections, this study demonstrates how Crowd Control evolved from a grassroots gathering of local creatives into a vibrant, collaborative network that reshaped the experience of open mic events. More than just a stage, Crowd Control became a platform where artistic expression intersected with community, connection, and resistance.

Collecting Feedback and Participant Reflections

To capture the impact of Crowd Control, I gathered feedback3 from participants, whose reflections revealed how the event fostered a sense of belonging and creative empowerment. Many described the open mic as a space where they felt heard and valued, echoing the principles of participatory culture. It was about more than just performing; it was about being part of something bigger, where everyone’s voice mattered. These reflections align with The Cultural Rhetorics Theory Lab’s assertion that “stories do important theoretical and cultural work,” highlighting how personal narratives shape and sustain community spaces. By centering diverse experiences, Crowd Control not only challenged dominant narratives within Dallas’s arts scene but also modeled how open mic events can function as sites of resistance and inclusion. This participant feedback underscores how the event provided a collaborative space where performers and audiences alike engaged in a shared act of meaning-making, reinforcing Crowd Control’s role as a site of cultural transformation.

Understanding Open Mics as a Platform for Expression

Open mic events, short for “open microphone,” provide public performance spaces where individuals can showcase their talents ranging from poetry, music, and spoken word to comedy and storytelling. These events offer low-barrier opportunities for both seasoned performers and newcomers to engage with an audience, fostering artistic exploration and community dialogue. Jessica Waffles, a prominent Dallas concert photographer, notes in KXT that “open mic nights serve as gateways to local music venues,” emphasizing that supporting these events helps sustain venues that are vital to the city’s cultural landscape by promoting local live music.4 While often associated with stand-up comedy, open mics extend beyond humor, serving as platforms for diverse forms of expression. Some events cater specifically to poets and spoken word artists, emphasizing rhythm, language, and narrative, while others highlight music or performance art, blending genres and styles. There were several very successful spoken word nights like Mad Swirl, Wordspace, DaVerse Lounge, Dallas Poetry Slam, and a number of groups working to uplift and empower the different communities that make up Literary Dallas.5 However, in 2017, Dallas offered few opportunities for cross discipline, multi-genre open mic nights. The city’s cultural landscape was shifting, with Deep Ellum, once a thriving hub for the arts, experiencing a lull in foot traffic and fewer opportunities for local shows. In this climate, Crowd Control emerged as a space where a variety of artistic voices could thrive, addressing a critical gap in the local arts ecosystem. JM, a frequent attendee and audience member, reflected that Crowd Control wasn’t “just for the cool kids in Dallas or pitched to one group. There were regular artists that came around but a lot of fresh faces. It was a welcoming community.”

Literature Review

Three key scholarly works inform this analysis of Crowd Control’s role as a reimagined urban creative space and its resistance to institutional barriers that restricted free expression in Dallas’s arts scene. Between 2016 and 2019, Dallas saw a rise in city-imposed restrictions on creative spaces, sparked by the Fire Marshal’s crackdown on venues supporting marginalized voices. Peter Simek, reporting for D Magazine, described how this shift affected the city's creative landscape. He explained that “Dallas had begun to foster a new kind of cultural identity for itself, as artists and cultural promoters took advantage of reclaimed or temporary spaces, rethinking the roles of traditional galleries, and staging events that deliberately cross-pollinated the worlds of music, art, and theater.” However, Simek noted that “stepped-up enforcement came after years in which the city had otherwise turned a blind eye to the arts community’s activity.” Local institutions like The Basement Gallery in Oak Cliff and the film production company Cinderblock Sessions in Fair Park were shut down due to issues with their Certificates of Occupancy.6 As a response, events like Crowd Control emerged as a direct challenge to these restrictions, fostering an inclusive, participatory environment that actively resisted efforts to silence artistic expression. Through our structure, our community engagement, and even our name—a tongue-in-cheek critique of crowd control measures historically used by police and government to suppress affirmative action and protest—Crowd Control pushed back against these restrictions, asserting the importance of creative freedom in the city’s cultural landscape.

Senda-Cook, Middleton, and Endres introduce the concept of rhetorical cartographies as a way to understand how communities counter-map urban spaces, reclaiming and reconfiguring environments to meet their needs. As Senda-Cook explains, “By approaching rhetorical cartographies with a participatory critical rhetorical lens, we can unpack the interactions inhabitants have in particular places and the rhetorical implications of the maps produced through those encounters.” Crowd Control operated within this framework, repurposing Mudsmith and later Sundown at Granada into inclusive, collaborative spaces where artists could challenge dominant narratives through their work. Our continued use of these venues transformed them into creative hubs, demonstrating how marginalized communities can reclaim urban spaces as sites of cultural production. In the context of increasing regulation that sought to limit unconventional artistic spaces, Crowd Control’s ability to redefine these environments underscored its role as a form of spatial resistance.

Cain’s work on individual participation in open-mic comedy performances provides further insight into the social dynamics that shape performative spaces. She highlights how audience-performer interactions create unique participatory cultures, noting that “Pekhonen’s description of 'choreography,' though highlighting interactional patterns across performances, demonstrates contingencies based on the particular performer and the performance witnessed.” At Crowd Control, similar patterns emerged. While some performers drew more audience engagement—often depending on whether they arrived alone or with friends—our space cultivated an overall atmosphere of warmth and support that encouraged first-time participants to return. This positive reception was essential for building a consistent community of artists and audiences, reinforcing the event’s role as a sustainable platform for emerging voices. As Dallas’s regulatory climate stifled opportunities for grassroots artistic expression, Crowd Control’s participatory culture provided an alternative space where artists could thrive despite external pressures.

Lambe’s analysis of queer open-mic spaces explores how amateur performance facilitates emotional expression, community-building, and resistance to normative structures. His work emphasizes that these spaces serve as sites of affective exchange and identity formation, where marginalized voices can assert their presence and redefine communal narratives. At Crowd Control, similar processes were at play. The event became more than just a performance venue; it was a space where artists could navigate personal and social identities, forge networks, and engage in acts of creative defiance. Lambe’s framework resonates with Mondada’s assertion that “in order to recognize and therefore describe the process through which audiences are constituted, it is crucial to deal with hearers as being as active as speakers.” This dynamic was evident at Crowd Control, where audience members played an active role in shaping the performative experience. Their engagement, support, and feedback were not passive; they were essential elements that sustained the space as a site of communal resistance and creative empowerment.

By drawing on these frameworks—rhetorical cartographies, participatory performance cultures, and affective exchange—this analysis demonstrates how Crowd Control stood as a bastion of creative resistance in Dallas’s shifting cultural landscape. At a time when city officials imposed constraints on artistic spaces, Crowd Control reclaimed urban environments and transformed them into platforms for free expression, fostering a community where diverse voices could flourish despite systemic efforts to suppress them.

Reimagining Space and Place

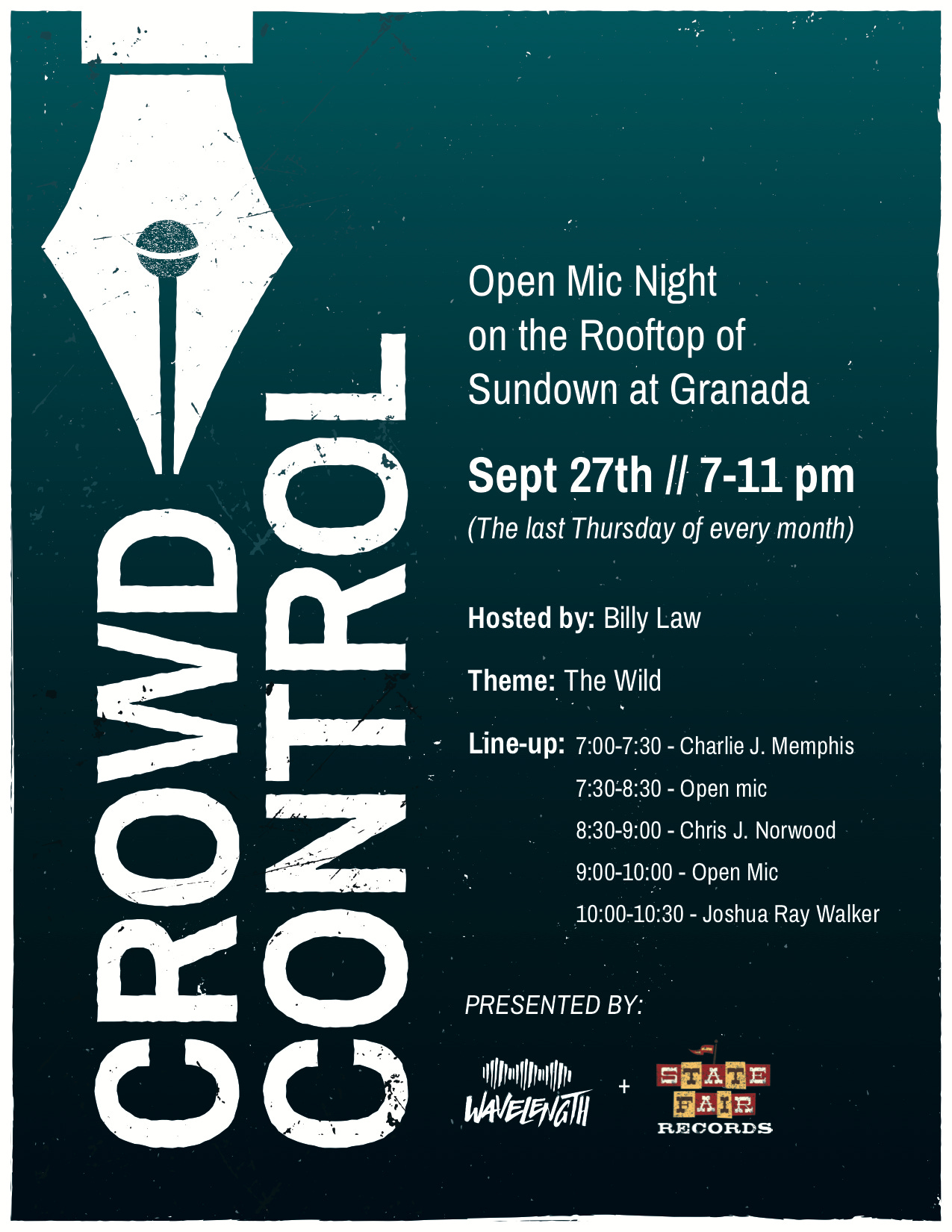

The framework for Crowd Control was designed to foster a unique and meaningful space for artists and the community. Held from 7:00 pm to 10:00 pm on the last Thursday of every month, the event intentionally operated on a monthly basis rather than weekly. This decision allowed participants the time and space to create new material, ensuring a fresh and engaging experience each time. While weekly open mics can sometimes feel repetitive, where regulars play the same songs or perform the same bits, the monthly format allowed artists to take risks and showcase their latest work. It also prevented the burnout that can happen when there is pressure to perform every week. From 7:00 pm to 9:30 pm, the event featured an open mic, where participants could sign up for a five-minute slot on a first-come, first-served basis. Time flexibility was built into the schedule to accommodate the ebb and flow of attendance, and the goal was always to avoid situations where someone would wait for hours only to miss their chance to perform. At 9:30 pm, the spotlight artist would take the stage for a 30-minute set. To keep the event accessible, there was never an entry fee—an intentional choice to eliminate economic barriers. To cover the spotlight artist’s fee, a $2 raffle ticket was sold, with the winner receiving a $50 gift card to the venue. While Will and I were not paid for running Crowd Control,7 and the spotlight artists often performed for a nominal fee, the energy and commitment of everyone involved made the event feel like a shared creative endeavor, and the absence of money as a driving factor contributed to its authenticity.

The decision to hold the open mic at Mudsmith was intentional—we sought to create an accessible, intimate space where artists could feel comfortable sharing their work. Coffee shops, traditionally spaces for conversation and idea exchange, offered a familiar yet adaptable environment that encouraged creativity. By repurposing Mudsmith as a venue for artistic expression, we challenged the conventional use of commercial urban spaces, transforming it into a energetic hub where poets, musicians, and comedians could experiment and collaborate. This aligns with Senda-Cook’s assertion that “while these are often temporary reconstructions, by engaging in deliberate, long-term, and repeated efforts to materially reconstruct urban places, such places can be invested with new meanings and reshaped to invite new practices.” Crowd Control embodied this transformative potential, as our consistent presence reshaped the space into one that prioritized inclusivity and artistic exploration. As ML, an attendee, described, it was “an incredibly welcoming and encouraging environment that embraced everyone.”

The open mic format of Crowd Control served as a platform for amplifying diverse voices within the Dallas arts scene. Ryker reflected on the event as “a cool gathering of songwriters and creative folks sharing all genres of music,” with the crowd being “receptive and attentive to all acts.” This echoes Cain’s argument that audience reception plays a crucial role in promoting engagement and shaping the overall experience of performative spaces. Positive audience interaction fed energy back into the space, creating a reciprocal environment where performers and attendees alike felt invested. This communal dynamic was pivotal in encouraging return participation and sustaining the success of the event. For participants like MG, who valued the opportunity to “meet other people . . . [and] perform,” and JM, who appreciated how Crowd Control provided opportunities to “newer artists that don’t get a lot of attention,” the event’s ability to support emerging talent across genres highlighted the power of space in facilitating creative expression.

MM’s reflection further underscores how the environment fostered a deeper sense of belonging: “The theme and dedication to the creation of art felt different. I feel like most open mics are an empty slate to impress your feelings upon, but the guidance shown by Britt and Will made it special by giving a sense of direction and community, one that felt more alive and special than other open mics.” While Will and I merely set the tone by establishing an inclusive, supportive environment, it was the people who returned month after month that truly shaped Crowd Control’s culture. They took ownership of the space, extending its welcoming ethos to newcomers. It was common to witness a regular attendee approach someone sitting alone—often a first-time performer—introduce themselves, offer words of encouragement, or exchange contact information. This organic, peer-driven engagement exemplifies what Lambe describes as the transformative potential of amateur performance spaces, where emotional expression and community-building resist normative structures and create new connections.

DVD captured this sentiment in his reflection: “This was my first experience playing any material live and they never made me feel out of place or inexperienced. I never felt embarrassed coming to them with any questions or tips outside of the show either. Definitely was a place I wanted to keep coming back to.” Similarly, Marco described how Crowd Control stood in stark contrast to other open mics where “the experience can sometimes feel awkward or uncomfortable, with a noticeable divide between newcomers and the usual cliques. But at Crowd Control, everyone felt included, whether they were performing or just there to support.” Mallory echoed this sense of inclusion: “I definitely felt like the dynamic was different at Crowd Control, mainly because I just felt so welcome and encouraged. I did not feel intimidated at all. And I felt like everyone was engaged and interested in each artist.” This sense of belonging and reciprocity reinforced the idea that Crowd Control was not just an event but a community—a dynamic space where social identity, creative expression, and activism intersected.

When Crowd Control outgrew Mudsmith and transitioned to Sundown at Granada8, we had to reimagine how space functioned within the event. The rooftop setting introduced new opportunities for engagement but also shifted audience dynamics. Moving from the intimate confines of an indoor coffee shop to an open-air rooftop altered the sensory and social experience of the event. However, the mission remained the same—to cultivate a space where artists could take risks, grow, and connect. This transition exemplifies how rhetorical cartographies evolve as communities navigate and repurpose urban environments to meet their needs. As Senda-Cook observes, “urban spaces are not static; they are constantly being reshaped by the people who move through them, embedding new narratives into the environment.” Even as the physical space changed, the culture and practices of Crowd Control endured, reinforcing the adaptability of creative rhetorical cartographies. Through consistent engagement, the community continued to infuse new meaning into Sundown at Granada, ensuring that the spirit of Crowd Control thrived in its new home.

Resisting Barriers and Creating Space

Crowd Control’s impact extended beyond serving as an open mic—it became a model for how artistic communities can challenge normative boundaries and reclaim urban spaces in cities where opportunities for free expression are often limited. As Senda-Cook observes, “We deploy an understanding of place-as-rhetoric to identify how urban space/place can be reconstructed to forge new identities and foster new rhetorical and material practices in those places.” Crowd Control embodied this principle by fostering a participatory culture where marginalized voices could thrive, allowing for the creation of new identities that pushed back against the structural limitations that had long restrained the Dallas arts scene. In 2017, as DIY venues and independent art spaces faced ongoing threats of closure, Crowd Control’s emergence highlighted how cultural rhetorics—through storytelling, community-building, and the reimagining of space—can actively reshape urban landscapes.

One of the most significant challenges in cultivating spaces that promote free expression lies in encouraging not just self-expression but genuine engagement with others. Crowd Control confronted this barrier by uniting participants around a common theme each month. Themes were proposed and voted on by attendees, allowing the community to shape the direction of each event. Additionally, competitions and collaborative elements encouraged deeper participation. As NMW observed, “There were the leavers, but there was no criticism or shame if you were, and over time, it fostered a community that seemed to come out every week!” This commitment to building engagement echoes Cain’s argument that the receptivity of a crowd plays a critical role in creating an environment that sustains creative expression. The supportive atmosphere cultivated at Crowd Control ensured that the space was not merely a platform for performance but a site of ongoing dialogue and shared experience.

Crowd Control also sought to dismantle the prevailing dominance of white, cisgender singer-songwriter spaces in Dallas. As Cain highlights, cultural landscapes often privilege certain voices while marginalizing others, and in 2016, the Dallas music scene reflected this dynamic. Although the city boasts a rich musical history—ranging from Robert Johnson’s legendary blues recordings at 508 Park Avenue to artists as diverse as Norah Jones, Erykah Badu, St. Vincent, Bobby Sessions, and Stevie Ray Vaughan—open mics had become uniform and insular, offering little opportunity for cross-genre performances or for underrepresented voices to be heard. It felt as though everyone was sticking to their own corner of the city. Crowd Control intentionally disrupted this pattern by embracing diversity across genres and identities. While this inclusivity was not explicitly planned in the beginning, our instinct was to create a space where all styles and backgrounds could be represented. As the event grew, we became more intentional in seeking out artists across genres to emphasize that Crowd Control was a space where “you can perform that genre here too.”9 This conscious effort allowed for a rich mix of performers—from rappers and singer-songwriters to comedians and spoken word artists—all sharing the same stage.

The success of Crowd Control’s multigenre approach is evident in the experiences of both attendees and performers, who consistently highlight its collaborative and welcoming atmosphere. Paul emphasizes the importance of such cross-genre interactions, noting, “we need to get back to inter-genre (for lack of a better term) collaborations among artists and performances.” This openness extended beyond artistic styles, fostering connections across racial, gender, and cultural lines. Davey reflects on the event’s unique energy, explaining that “although it was an open mic, it served a different purpose. It felt more like a collective that started and ended its life cycle every night.” Similarly, Mallory underscores the creative freedom and support that defined the space, observing that “it wasn’t just one style or genre of music performed. It was a great place to explore, experiment, and support one another.” Tara, who played a key role in facilitating Crowd Control’s move to Sundown at Granada, reinforces this sentiment by describing the environment as “fun, all [were] welcome, [a] community. Artists supported each other. Shared ideas. It was about the music and the creativity. Letting people be themselves and being expressive. People drove from all over to be a part of it. Some even from other cities and states.” Collectively, these reflections reveal how an open mic event can transcend typical boundaries, transforming open air spaces into dynamic places where creativity can flourish and bring diverse voices together.

The influence of Crowd Control extended beyond the event itself, inspiring other artistic spaces and contributing to a broader cultural shift. JRM noted, “The libretto for ‘Faces of Dallas,’10 which I helped curate, could not have happened without the example set by local interdisciplinary arts programming like Crowd Control.” He further emphasized how “spaces (or space-time continuums) like Crowd Control create spaces in which people can explore their many possible affinities. Deep awareness of those affinities can, in turn, help us better understand our differences.” This echoes Burke’s notion of identification and consubstantiality, where shared experiences in a communal space enable participants to recognize both their similarities and differences, fostering a more inclusive environment. As Burke states, "A is not identical with his colleague, B. But insofar as their interests are joined, A is identified with B. Or he may identify himself with B even when their interests are not joined, if he assumes that they are, or is persuaded to believe so." Burke’s exploration of these ideas provides a framework for understanding how shared experiences within a communal space can forward inclusivity while acknowledging differences

As Crowd Control gained momentum, it became a vital incubator for a new generation of Dallas artists. CBW described how, “Crowd Control came at a vital time in the Dallas music scene. It may have just been my experience or my first glimpse of a scene that already existed, but Crowd Control was kind of an intro/kickoff for that specific 'generation’ of DFW artists/songwriters. When Crowd Control was starting, I feel like everything was beginning for so many musicians. It was the beginning of careers. Crowd Control was the perfect outlet in those beginning stages. In a way, it lit a fire under all our asses.” For many artists, Crowd Control provided a sense of accountability, encouraging them to show up each month with fresh material. The opportunity to engage with other artists and writers served as a powerful motivator, driving their creative growth. As MG reflects, “Seeing everyone else doing the thing is always beneficial. Even though I can be solitary in my work, it was great seeing others just as passionate.” This sentiment underscores how environments like Crowd Control not only inspire individual artists but also cultivate a thriving artistic community, where shared passion and collective energy fuel creative development and shape the trajectory of local arts scenes.

Though the dynamics of the Dallas arts scene shifted in the aftermath of COVID-19, the legacy of Crowd Control endures. As CBW reflected, “Though things changed post-COVID, the legacy, warmth, and community of Crowd Control undoubtedly lives on and continues to encourage careers in so many.” This success demonstrates that by resisting barriers, fostering inclusivity, and creating space for diverse voices, grassroots artistic communities can reshape cultural landscapes and leave a lasting impact.

Shared Goals and Collaborative Networks

Crowd Control was fundamentally designed to cultivate original artistic content while fostering a space where participants could build confidence, overcome creative blocks, and discover solidarity among fellow artists. This mission was reinforced by our use of monthly themes, which encouraged participants to create new material inspired by shared prompts. Themes like Echoes, Indecision, and Trial by Fire provided a unifying thread that linked individual artistic efforts into a collective experience.11 Marco, reflecting on his first time performing, recalled, “[It] had such a warm and inclusive vibe. The first time I performed at one was on the upstairs patio at Sundown, and I remember being amazed by the talent there. You could feel that everyone was in their element, freely expressing themselves in a safe and supportive space. It was truly a special experience.” His experience highlights how these creative prompts transformed Crowd Control from a simple open mic into a collaborative environment where participants drew inspiration from one another and built a community of practice.

This collaborative spirit positioned Crowd Control as a dynamic discourse community in line with John Swales’ framework. Participants shared a common goal: to resist the erasure of marginalized voices and to cultivate an inclusive space where artistic expression was celebrated. Feedback from attendees underscored the significance of this community-driven ethos. Crowd Control wasn’t just about getting on stage, it was about feeling seen and heard in a city where finding space for that wasn’t always easy. This sentiment reinforces the argument from the literature review that storytelling and shared experiences are central to cultural rhetorics, serving as tools for understanding, resisting, and reimagining societal norms. Through the convergence of storytelling, poetry, music, and other forms of expression, Crowd Control created an environment where diverse voices could thrive and where artistic exploration was both welcomed and nurtured.

Moreover, Crowd Control fostered a collaborative network that extended beyond performance. Only several occasions we had the privilege of collaborating with local organizations to co-present events, including State Fair Records in September 2018, Beats By Her in May 2018, and Palo Santo Records in April 2019. These events served as a microcosm of knowledge exchange and mentorship, where experienced artists and newcomers engaged in mutual learning. Social dynamics emerged organically, with regular attendees assuming informal leadership roles by offering feedback and encouragement. This structure echoed the grassroots nature of urban cultural movements, where creative communities reconfigure traditional hierarchies to prioritize accessibility and growth. Lambe articulates this dynamic, noting that “open mic spaces serve as microcosms of resistance and affirmation, where individuals can redefine themselves through creative expression.” By encouraging relationships between seasoned and emerging artists, Crowd Control built an ecosystem where artistic development flourished through communal support and mentorship.

Inclusivity was central to Crowd Control’s mission. We aimed to create an environment that resisted hegemonic structures related to gender, class, and race, breaking away from the rigid expectations often imposed by traditional performance spaces. The open mic format enabled a wide range of voices to be heard, while the informal, welcoming atmosphere reduced the intimidation often associated with public performance. Paul, reflecting on his experience, noted, “I thought it was a very welcoming community of individuals all looking to improve their craft while also coming together socially.” Crowd Control’s commitment to lowering barriers to entry and fostering an inclusive space empowered marginalized voices to share their work and engage with a broader creative community.

The act of reclaiming urban space for artistic expression was itself a form of resistance. By transforming Mudsmith and later Sundown into creative enclaves, Crowd Control disrupted the commercial, consumer-driven nature of these venues, repurposing them as platforms for community-driven storytelling and artistry. As Colby Charles observed, Crowd Control was “the first place I felt safe and welcomed sharing my poetry outside of my home,” underscoring the event’s role in fostering a sense of belonging and inclusion. Similarly, Bayleigh, who performed as the spotlight artist in May 2018, remarked, “It was a great place to meet other fellow musicians who all shared the same goals and were able to build a community.” Ryker also described the crowd as “attentive and respectful.” These reflections emphasize how Crowd Control’s collaborative spirit and commitment to inclusivity created an environment where diverse voices and artistic expressions could flourish, leaving a lasting impact on the Dallas arts scene.

Final Thoughts

Crowd Control exemplifies how cultural rhetorics come to life in urban environments through the intentional reimagining of space. By transforming Mudsmith and later Sundown at Granada into hubs for artistic collaboration, we redefined the typical use of commercial venues, creating a space rooted in inclusivity and creative freedom. As Westonn observed, Crowd Control provided “a place for artists to freely express themselves . . . It was chill and inviting, something so important for first-time visitors and first-time performers.” This insight highlights how reimagined spaces can create a lasting cultural impact, uniting artists from diverse backgrounds and disciplines.

The impact of Crowd Control extended beyond its physical transformation of spaces, it became a symbol of the resilience of creative communities that refuse to be silenced. In redefining “crowd control” from a term associated with suppression into one of empowerment, Crowd Control demonstrated how storytelling and communal participation can break down barriers and provide a platform for artistic expression.

Personally, Crowd Control was integral to my own identity and creative journey. It profoundly shaped my ability to open up to others, to be vulnerable in my creativity, and to trust my peers for both support and collaboration. Through this space, I learned the power of shared experiences, how to navigate vulnerability, and how to connect with others on a deeper, more meaningful level. Crowd Control was not just a venue for art—it was a lifeline that fostered kinship and mutual trust, something I carry with me to this day.

References

Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969.

Cain, Sarah Seewoester. When Laughter Fades: Individual Participation during Open-Mic Comedy Performances. PhD diss., University of Missouri, 2018. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/when-laughter-fades-individual-participation/docview/2572642907/se-2.

Clemans, Shantih E. “Open Mic: Reciprocity, Parallel Process, and Mutual Aid in a Discussion Group for Faculty Working with Adult Students.” Social Work with Groups 44, no. 1 (2021): 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2020.1748556.

Cranford, Steve. “All Voices Welcome at Matter ‘Open Mic.’” Matter 5, no. 8 (2022): 2383–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matt.2022.07.007.

Holt, E. “After Cracking Down on DIY Music Venues, Fire Marshals Have Turned to Small Art Gatherings.” Dallas Observer, February 1, 2017. https://www.dallasobserver.com/arts/after-cracking-down-on-diy-music-venues-fire-marshals-have-turned-to-small-art-gatherings-8490378.

Lambe, Ryan J. Performative Space/Transformative Space: Race, Affect, and Amateur Performance in US Queer Open Mics. PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2023. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/performative-space-transformative-race-affect/docview/2812358684/se-2.

Mondada, L. “BEcomING Collective: The Constitution of Audience as an Interactional Process.” In Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, edited by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, 876–883. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005.

Pehkonen, S. “Choreographing the Performer-Audience Interaction.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 46, no. 6 (2017): 699–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241616636663.

Senda-Cook, Samantha, Michael K. Middleton, and Danielle Endres. “Rhetorical Cartographies: (Counter)Mapping Urban Spaces.” In Field Rhetoric: Ethnography, Ecology, and Engagement in the Places of Persuasion, edited by Candice Rai et al., 95–119. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2018.

Simek, Peter. “The Fire Marshal Wants to Shut Down Our Party.” D Magazine, December 1, 2016. https://www.dmagazine.com/publications/d-magazine/2016/december/the-fire-marshal-wants-to-shut-down-our-party/.

Simek, Peter. “Why Is the Dallas Fire Marshal Harassing the City’s Arts Scene?” D Magazine, July 25, 2016. https://www.dmagazine.com/politics-government/2016/07/why-is-the-dallas-fire-marshall-harassing-the-citys-arts-scene/.

Waffles, Jessica. “Resolved to Hear More Music? Try One of These 35 Open Mic Nights in DFW.” KXT 91.7, January 2, 2024. https://kxt.org/2024/01/resolved-to-hear-more-music-try-one-of-these-35-open-mic-nights-in-dfw/.

Notes

For additional background on Crowd Control and a full list of the spotlight artists who performed, visit Wavelength Magazine.

Crowd Control began in May 2017 after a chance encounter at Mudsmith sparked its creation. Jim Fitzgerald and I were catching up with our friend Macon, a former Mudsmith barista and host of the previous open mic, Filtered. Macon had moved on to pursue music and travel but suggested that Jim and I take over the open mic in his absence. Though interested, we hesitated to commit. Two days later, I received a call from Joshua Ray Walker, who had also spoken with Mudsmith about reviving the open mic through his production company, Balero Productions. This connection introduced us to Will Latham, a longtime friend and bandmate of Josh’s in Ottoman Turks. Although I hadn’t met Will before, our visions aligned—focusing on original content and fostering experimentation. With Jim managing sound, Will (Billy Law) hosting, and me coordinating production, Crowd Control came to life.

Responses were collected through a shared Google Doc distributed to participants and attendees. I curated a series of guiding questions across four categories: Creation of Space, Audience Engagement and Participation, Collaboration and Networking, and Community and Artistic Identity. Since Crowd Control was founded on a collaborative spirit where participants shaped its culture, I aimed to extend that ethos to the feedback process. The shared document allowed participants to provide feedback anonymously or include their names. They could also read and engage with others’ responses, which might have sparked memories or encouraged agreement or disagreement. While I recognize that a public forum may have discouraged some from offering critical feedback, I hoped that the option for anonymity encouraged participants to share their honest experiences. A link to the full survey is included.

For a contemporary list of Dallas open mic nights, check out Jessica Waffle’s article on KXT. It also includes some helpful tips about open mic etiquette.

#LiteraryDallas emerged in early 2014, coinciding with a wave of exciting literary initiatives such as the Pegasus Reading Series, Common Language Project, Young DFW Writers, Writer’s Garret, Dallas Poetry Society, Woman Galore, Dark Moon Poetry, the launch of The Wild Detectives and Deep Vellum. This period marked a spirited moment in Dallas’s literary scene which has only continued to foster diverse voices and creative communities.

The Dallas Observer reported that on June 30, Cinderblock was preparing for a session with Jonas Martin when a city code inspector arrived unannounced and threatened to shut down the performance. The inspector emphasized that any activity outside the building's zoning, even a single event, could jeopardize Cinderblock's zoning and permitting rights. Despite allowing the session to continue with the understanding that paperwork would be addressed later, another officer arrived, warning that future events could lead to intervention from the district attorney, fire marshal, and police. Cinderblock had a photography warehouse CO but was working on securing the required amusement indoor CO.

A few months after relocating to Sundown at Granada, we negotiated to receive 10% of the upstairs bar sales during the event. It wasn’t much—in fact, I don’t think we ever made more than $100 on any given night—but it was enough to cover the spotlight artist’s fee if raffle ticket sales fell short of the $50 threshold.

We hosted events at two locations: Mudsmith from July 2017 to April 2018 and Sundown at Granada from May 2018 to October 2019. Initially, we operated under Joshua Ray Walker’s Balero Productions at Mudsmith, but after moving to Sundown at Granada, we transitioned production under Wavelength Magazine, our cultural arts publication.

Crowd Control proudly hosted a wide range of performances, spanning across various genres including singer-songwriter, folk, hip hop, stand-up comedy, spoken word, slam poetry, alternative, country, bedroom pop, indie rock, and even electronic music. As the event moved to the rooftop of Sundown at Granada, we attempted to kickstart an After Hours event that featured local DJs and electronic acts. Unfortunately, our network within that community wasn’t strong enough to drive the promotion, and the Thursday night time slot from 10 pm to midnight proved difficult for our audience to embrace. Despite these challenges, we are forever grateful to IAMYU and BOUT for stepping in as the beta testers of the After Hours concept. Their performances and support during that phase were invaluable, and I’m proud to see both artists go on to build incredible careers. It was a privilege to work with them, and I’m thankful for the opportunity.

Faces of Dallas highlights the diverse and passionate individuals who shape the city's cultural landscape, capturing the unique stories and personalities that contribute to its dynamic community. Through portraiture and storytelling, it reflects the heart of Dallas, showcasing the people who make it thrive.

Each month, I created a rudimentary word map centered around a theme to serve as a creative jumping-off point for participants. The inspiration for these word association maps came from a SXSW interview with director Harmony Korine while he was promoting his 2009 film, Trash Humpers. The complete list of themes, in order of appearance, includes: Love, Dreams, Regret, Time, Going Home, Dissociation, Insignificance, Frequency, Denial, Running Away, Edges, Clarity, Memory, Disaster, The Wild, Terror, Innocence Lost, Undercurrents, Renewal, Deception, Circumstance, Mirrors, Illusion, Escape, Trial by Fire, Endurance, Indecision, and Echoes.